Silverpoint has been undergoing a second renaissance since its rescue from oblivion in the early 19th century. Its latest versions, some of which I have been talking about in the current Evansville Museum of Arts Luster of Silver exhibition, show that it still has a lot of vigour and zest. It was largely forgotten after the discovery of graphite supplanted silver during the late high Renaissance. Silverpoint was rediscovered in the early 1800s when Cennino Cennini's 1390 manuscript of Il Libro dell'Arte was found in the Laurentian Library in Italy. Readers of the first printed edition learned of this drawing medium in 1821. Many artists tried their hand at silverpoint, but the advent of abstract and non-figurative art in the mid-20th century virtually banished the medium.

In recent years, silverpoint is slowly regaining its luster, thanks in large part to Dr. Bruce Weber, presently Director of the National Academy Museum. In 1985, he curated a ground-breaking silverpoint exhibit, The Fine Line. Drawing with Silver in America, at the Norton Museum in West Palm Beach, Florida. (The catalogue of that exhibit has since acquired a cult following amongst silverpoint aficionados!) with silverpoint back on the map, artists took note. Today, the number of silverpoint artists is increasing. The medium is now being taught and covered by the art print media and Internet, with the important Silverpointweb.com becoming a clearing house for information on the medium.

The first Luster of Silver 2006 survey of contemporary silverpoint, curated by Holly Koons McCullough at the Telfair Museum of Art in Savannah, Georgia, was testimony to the medium's renewed vigour. While most full-time silverpoint artists often follow the centuries-old techniques (which include using gold, copper, platinum and other metals in addition to silver), they are nonetheless pushing the medium out to new boundaries. Combining different media with silverpoint is technically difficult. But it is happening, and it demonstrates the medium's ability to reflection and respond to today's complex and challenging world.

I frequently combine silverpoint with touches of watercolour, a balancing one-chance act when working on an acrylic ground. But it fun to try these combinations for new effects.

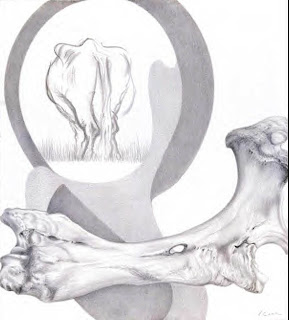

The watercolour can be applied traditionally in liquid form (difficult and not always stable on the acrylic ground). In this example, Marianna's Gift,

the silverpoint drawing is on a tinted ground. The highlights are placed in with white gouache, an opaque form of watercolour. Adding the darkened touches of red watercolour straddled the old and the new forms of silverpoint. Many Renaissance drawings were on tinted grounds.

the silverpoint drawing is on a tinted ground. The highlights are placed in with white gouache, an opaque form of watercolour. Adding the darkened touches of red watercolour straddled the old and the new forms of silverpoint. Many Renaissance drawings were on tinted grounds.(I will continue this discussion about New Horizons for Silverpoint tomorrow....)

+-+silverpoint.jpg)